Annotations Issue 35: Governing the Hydra - Why AI Alone Won’t Solve Content Moderation

The dilemmas around what to moderate, how much to intervene, and who gets to decide remain as fraught as ever—and now operate behind even murkier algorithmic walls.

Dear readers,

Congratulations to the Great Class of 2025! From those of us staying at JPIA, we wish you the best as you embark on the next adventure ahead – we’re excited to see what amazing things you will accomplish and the change you will bring with you wherever you go!

In this week’s edition, Carolina G. Azevedo (MPP ‘25) highlights the ever evolving challenge of content moderation and the complications of using artificial intelligence in moderation practices. Today, as AI becomes ever more entrenched in moderation practices, it is tempting to view automation as a neutral fix. But the dilemmas around what to moderate, how much to intervene, and who gets to decide remain as fraught as ever—and now operate behind even murkier algorithmic walls.

As always, send us your questions, ideas, pitches, comments, or thoughts! And for our alums and the newly graduated, don’t forget to write to us too. As policy students, right now is an important moment to speak out – Annotations exists as an outlet for you to do so. Write to us at jpia@princeton.edu or check out our submission guidelines!

Happy reading!

Michelle, Mera & Paco

JPIA Digital Editors

Governing the Hydra: Why AI Alone Won’t Solve Content Moderation

by Carolina G. Azevedo '25 for Annotations Blog

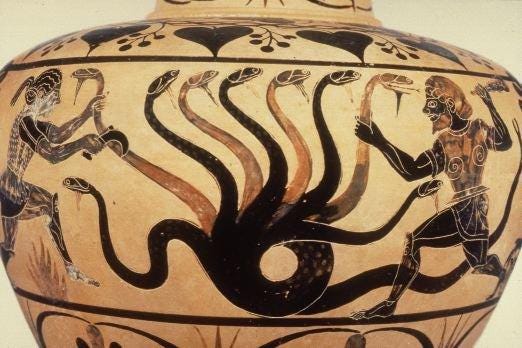

In classical mythology, the Hydra was a serpent-like creature that grew two heads for every one severed. Tackling content moderation in the digital age—especially through artificial intelligence (AI)—feels just as daunting. Every “solution” generates new problems, raising hard questions about free expression, democratic integrity, and corporate responsibility. The promise that technology alone could “solve” content moderation has proven false. Instead, what we confront is a wicked problem: value-laden, recursive, and defined by inescapable tradeoffs.

Today, as AI becomes ever more entrenched in moderation practices, it is tempting to view automation as a neutral fix. But the dilemmas around what to moderate, how much to intervene, and who gets to decide remain as fraught as ever—and now operate behind even murkier algorithmic walls.

Drawing the Line: Freedom versus Harm

The clearest global consensus around moderation involves illegal content, such as child sexual abuse material or terrorist incitement. However, even when it comes to the clearest-cut issues, enforcement at scale is daunting.

In the realm of harmful but legal content, consensus fractures. Hate speech, disinformation, harassment—these are often legally protected under broad free speech interpretations in the U.S., a tradition shaped by Justice Louis Brandeis’s famous call for "more speech" rather than censorship.

Elsewhere, notably in Europe, the legal landscape differs. Holocaust denial is criminalized in Germany and France, for example, but remains protected in the U.S. During a recent visit to Princeton University, Brazilian Supreme Court Justice Luís Roberto Barroso captured the tension succinctly: "Freedom of expression is not the freedom to destroy democracy."

This divergence forces global platforms like Meta and TikTok into politically charged decisions. What is permitted in one jurisdiction may be intolerable in another. And as Harvard’s Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt warn, when traditional gatekeepers weaken, authoritarianism can emerge through seemingly democratic means. The stakes of moderation decisions, once seen as technical, are now existential for democracy itself.

Efforts to prevent harm must also grapple with a difficult truth: genocides do not begin with weapons; they begin with words. The United Nations has emphasized this link through its campaigns against hate speech, highlighting how unchecked incitement can erode societal norms and enable mass atrocities. Content moderation, therefore, is not just about preserving civility—it is about protecting fundamental human rights and democratic stability.

Cutting Too Deep or Not Enough

Moderation strategies also confront a tradeoff between too much intervention and too little. Overzealous takedowns can suppress dissent and drive users to radical alternative platforms. Under-moderation, meanwhile, allows extremism and misinformation to metastasize, sometimes with deadly real-world consequences.

This dynamic echoes the Hydra metaphor: every time a major platform enforces stricter rules, some users migrate to alternative networks with looser moderation standards. In recent years, alternative social media platforms have emerged as havens for those seeking fewer restrictions, illustrating how attempts to curb harmful content in one space can unintentionally multiply challenges elsewhere.

New approaches emphasize the need for system-level thinking. Legal scholar Evelyn Douek, for instance, argues that content moderation must move beyond reactive post-by-post takedowns toward shaping the upstream architecture of platforms: What goes viral? What gets recommended? Designing for safety, legitimacy, and transparency from the start matters far more than any individual takedown decision.

The Double-Edged Sword of AI Moderation

Facing billions of posts daily, platforms have scaled themselves into dependence on AI. Media scholar Tarleton Gillespie captures this reality bluntly: "Content moderation is the commodity that platforms sell." Full AI systems, machine learning models, and algorithmic filters now underpin most moderation work. This automation is essential but imperfect.

As highlighted in AI Snake Oil by Arvind Narayan and Sayash Kapoor, AI moderation brings both promise and peril. AI enables real-time flagging and protective triaging of harmful material, and it shields human reviewers from the worst traumas of social media. Yet it stumbles badly on context, satire, and cultural nuance. Worse, AI systems can embed existing biases, leading to uneven enforcement that disproportionately harms marginalized communities.

Newer AI models show improvement, especially with multimodal tools that combine text and image analysis. But even the best systems still generate false positives, taking down legitimate speech, and false negatives, missing dangerous content. In short: without AI, moderation is impossible. With AI alone, it is unreliable.

Content moderation, therefore, is not just about preserving civility—it is about protecting fundamental human rights and democratic stability.

Opacity and the Crisis of Trust

A deeper problem underlies all these tradeoffs: opacity. Users often cannot see how moderation decisions are made, or even who is making them. Platforms like Meta have publicly moved toward "community-driven" moderation through initiatives like Community Notes. Yet behind the scenes, AI models still quietly rank, flag, and demote content according to secret internal thresholds.

Contrast this with Reddit’s model, which sometimes offers users a “nudge” to revise posts before takedown—a small friction that preserves agency and creates visible decision trails. Reddit’s approach may not scale as easily, but it better reflects democratic values of transparency and participation.

Attempts to bring more openness face fierce resistance. When researching this article, I approached Meta professionals working on AI content moderation. Both declined interviews, citing the "sensitive environment." Bluntly, they hinted that no one was going to speak to me about this right now.

Toward Governing the Ungovernable

The wickedness of content moderation lies precisely in its lack of clean solutions. The idea of courts or governments regulating speech sounds reassuring, but state actors are not always protectors of human rights. Takedown demands can come as easily from autocrats as from democrats. And platforms, driven by profit and engagement metrics, are poor stewards of democratic discourse left to their own devices.

Social media today is not built for security by design. It is built for addiction by design—optimized to capture attention (which is profitable), not to protect users. As Anthropologist Natasha Dow Schüll once described the architecture of machine gambling, today’s platforms are finely tuned to maximize engagement, not democratic deliberation, transparency, or safety.

What we face, then, is not a problem to be solved but a space to be governed—messily, imperfectly, but, essentially, transparently.

The Hydra cannot be slain. But it can be governed—if we stop pretending it’s invisible.

Meet the Author: Carolina G. Azevedo

Carolina G. Azevedo is a 2025 Master's in Public Policy graduate from Princeton University, where she focused on science, technology, and environmental policy. She also holds an MSc in Development Studies from the London School of Economics and an MBA from Fundação Getulio Vargas in Brazil. A former journalist, she has worked at the United Nations for over 19 years, from building trust during Colombia’s historic peace process to boosting transparency and impact storytelling for the Sustainable Development Goals.