Annotations Issue 37: Developing resilience: Why investment in global social protection matters now more than ever

In a shifting development landscape, governments and funders must stay committed to expanding the coverage and adequacy of social protection programs.

Dear readers,

The first issue of the school year is in! Sarah Bryant (MPA ’26) makes the case for international investment in global social protection. As aid budgets remain constrained, she lays out the impact of investing in digital infrastructure and labor mobility programs for social protection. Bryant argues that replacing regressive subsidies with social protection programs can stimulate economic growth in a more equitable and environmentally sustainable way.

You have such good thoughts, and we want to hear them! Send us your questions, ideas, pitches, comments, or thoughts –– write to us at jpia@princeton.edu or check out our submission guidelines.

Mera (MPA) and Michelle (PhD)

JPIA Digital Editors

Developing resilience: Why investment in global social protection matters now more than ever

by Sarah Bryant '26 for Annotations Blog

The Trump administration’s dismantling of the US Agency for International Development (USAID) earlier this year marked the start of a new era in foreign aid, with a transactional approach and short-term objectives dictating US spending abroad. Other bilateral donors are following suit, with the UK, Germany, Canada, and others cutting up to 39% of their aid budgets for 2026. Development organizations around the world are under pressure to demonstrate that every dollar spent and program executed is a good investment. As governments and aid practitioners make difficult decisions about where to focus limited resources, social protection programs ought to remain at the forefront as a necessary and effective response to the global demographic transition, economic inequality, and the climate crisis.

The investment case for social protection

Over the last decade, 4.7 million people gained access to social protection (SP) programs, including social safety nets, social insurance, and labor market programs. However, SP coverage remains at its lowest where it is needed most: among the poorest households in poorer countries. At the World Bank this summer, I worked with the Social Protection and Labor Global Practice on the Bank’s efforts to close this gap by reaching 500 million more people with SP by 2030.

To achieve this goal, the Bank is making the case to both donor and recipient governments that SP programs are worthwhile. Social assistance has a high community impact: every dollar transferred to families that need it most has an estimated multiplier effect of $2.50 in the local economy. Moreover, SP programs help households escape poverty, unlock employment opportunities, and handle crises such as extreme weather or job displacement by automation. A robust, well-designed safety net enables individuals to move from survival to self-reliance.

Global demographic shifts make the SP agenda even more urgent. In the developing world, youth populations are booming. The working-age population of low-income countries will increase by 1.4 billion by 2050, out of which 40% (560 million) are unlikely to find living wage jobs in their home country. Developed countries face the opposite problem: their rapidly aging populations will strain care services and pension systems. SP policy gives us the tools to address both challenges through social pensions, economic inclusion and labor market programs, and adaptive transfers that lighten the impact of unexpected shocks.

Emerging SP policy: Digital transformation and labor mobility

To expand coverage and scale up SP programs in low- and middle-income countries, we need strategies to reach more people at a lower cost. Two emerging areas in SP policy design hold promise to meet the current moment in international development.

Digital transformation and digital public infrastructure

Effective social protection requires adaptive delivery systems that enable policymakers to both identify people’s needs during normal times and quickly respond to shocks and crises – from natural disasters, to conflicts, to aging and job transitions. The World Bank and its partners help countries develop dynamic social registries, digital payment systems, and other digital tools for program targeting and administration. For instance, the Bank, in collaboration with Germany and Switzerland, created free, open-source software to improve the management of SP financing schemes in low- and middle-income countries. This initiative communicates an important message: digital tools are the technical backbone of scalable, transparent, and efficient SP delivery systems, and as such, they should be treated as digital public goods. This is not only a noble principle; it also makes financial sense. When development actors invest in interoperable system blueprints, it reduces the cost of digitalization for any single country.

NGOs have also taken up this challenge. Co-Develop, a non-profit fund that makes targeted investments to help countries accelerate digital transformation, defines digital public infrastructure (DPI) as the society-wide digital capabilities that are essential for participation in society and markets. In Co-Develop’s model, instead of governments building proprietary technology, they create interoperable, reusable building blocks, which enable rapid application of the technology to a new use case. For example, a case management system designed for a cash transfer program could be used to administer support amid worsening drought conditions or in response to the next pandemic. Digitalization is already underway; we must now ensure that tomorrow’s digital tools are inclusive, interoperable, and publicly accountable.

Labor mobility and Global Skill Partnerships

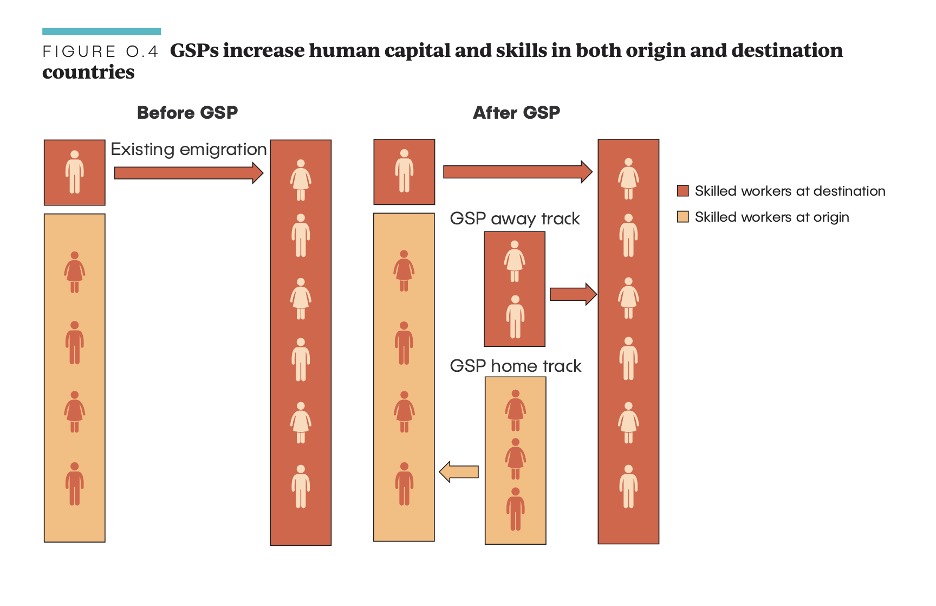

For political and logistical reasons, labor mobility has been less prominent in social protection policy. And yet, the growing number of workers without jobs in the developing world matched with labor shortages in developed countries means labor migration is a phenomenon that cannot be ignored. Earlier this year, the World Bank published a report on Global Skill Partnerships (GSPs), a bold solution to cross-border labor mobility that advocates for shared responsibility among countries to invest in a global pool of talent. GSPs recognize that in high-income countries with an aging population, the issue is not just missing workers but also missing human capital. Their shrinking workforces lack the skills and training opportunities to meet demand in key sectors, such as the care and nursing industries. Through bilateral GSP agreements, firms and governments of the more developed destination country finance training for workers in the less developed origin country, some of whom then stay home while others emigrate. The supply of skilled workers in the origin thus increases with the training of non-migrants, while destination countries benefit from an inflow of skilled migrant workers.

GSP implementation is fraught with challenges, but successful countries and organizations are leading the way. Germany’s GSP with the Philippines has trained and placed 6,000 highly qualified Filipino nurses in both countries while implementing safeguards to protect worker rights. From civil society, the LaMP Forum coordinates employers, responsible recruiters, workers, and governments in specific migration corridors and sectors to achieve better labor migration outcomes. Labor mobility must be included in the SP agenda if we are to create a future with mutually beneficial and well-managed migration.

The path forward

Even as governments recognize the importance of social protection for their development goals, global aid cuts continue to constrain the actions they can take on digital transformation, labor mobility, and other key areas. At the domestic level, subsidies are prime candidates for fiscal reallocation. Subsidies for fossil fuels, agriculture, and fisheries likely exceed $7 trillion annually worldwide and are often regressive, inefficient, and environmentally unsound. Replacing regressive subsidies with targeted transfers could generate fiscal space for SP programs while simultaneously meeting climate and equity goals.

In today’s development landscape, the path to universal social protection requires hard work and political courage. A commitment to more and better social protection is necessary from governments, multilaterals, and NGOs alike to meet the challenges of tomorrow and forge a more resilient and prosperous future for all.

Meet the author: Sarah Bryant

Originally from Nashville, Tennessee, Sarah completed her undergraduate degree in international politics and Latin American Studies at Georgetown University. Before graduate school, she worked for a D.C.-based global strategic advisory firm, where she researched political and economic trends in northern Latin America to provide market risk guidance to corporate clients and advance U.S. commercial diplomacy. Past experience as a research assistant for a database on Latin American institutions and as an intern at a refugee resettlement nonprofit affirmed her passion for public service, migration policy, and Western Hemisphere affairs. After her first year at SPIA, she joined the World Bank's Social Protection and Labor Global Practice to support a grant program on digital social protection and develop practice-wide portfolio and strategy documents. In her free time, Sarah enjoys running, trying new recipes, and collecting houseplants.